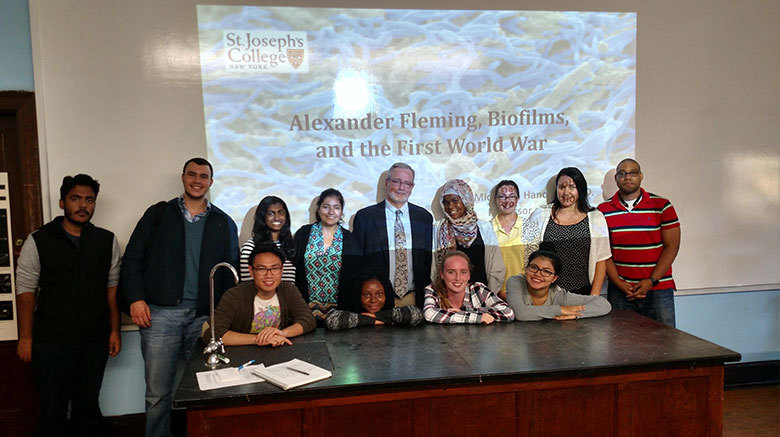

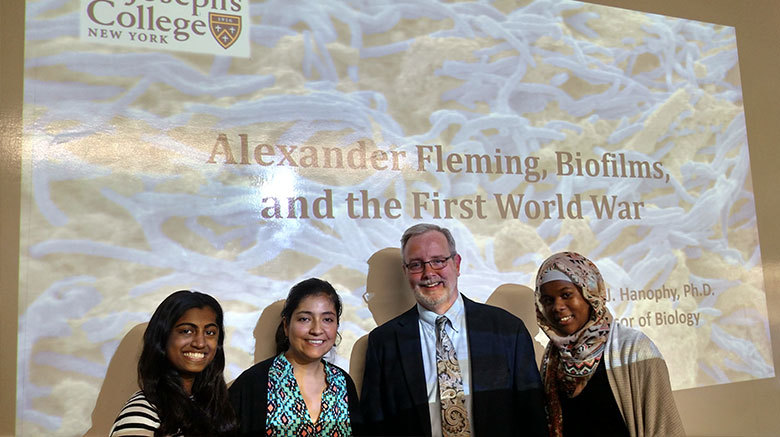

SJC Brooklyn biology professor Michael Hanophy, Ph.D., presented a lecture Oct. 18 on the origin of biofilm among the backdrop of World War I, as researched by Alexander Fleming — a influential scientist most famous for his discovery of penicillin.

A Different Battleground

Dr. Hanophy examined a brief history of infection during warfare, and the attempts to cure it.

From the dank, farm fields in the European battlegrounds of World War I came a rise in gangrenous wounds. Treated by antiseptics, bleach and other ineffective forms of patchwork gauze, these wounds would provide the basis of biofilm — a term which would not be used until the 1970s.

A biofilm is any group of microorganisms in which cells stick to each. Often these cells adhere to a surface — in this case, a layer of bacteria on soldiers’ uniforms. After explaining biofilm and its properties to the students, Dr. Hanophy went on to showcase Sir Alexander Fleming — a Scottish biologist who would make great leaps in immunology in his attempts to to cure biofilm-related infections.

Diagnosing the Cure

Biofilm’s significance during World War I injuries was due to two factors: the types of weapons used which embedded shrapnel and created complex, ridged wounds in soldiers; and the wet, bacteria-embedded terrain. Soldiers wearing muddy uniforms would find themselves infected when an explosive device ripped through their garments, embedding harmful bacteria within their lacerations.

Fleming concocted an innovative experiment — an artificial wound. By blowing glass at the bottom of a beaker to create jagged receptacles at the base, Fleming effectively created his own shrapnel wound. Fleming placed bacteria within the cavernous recesses of the beaker, then attempted to clean the beaker using traditional antiseptics.

When this method exacerbated the spread of bacteria, Fleming was able to explain why antiseptics were killing more soldiers than the infections themselves during World War I. Fleming noted that the injuries of soldiers harbored biofilm that was devastating to the body.

Fleming’s work proved to be greatly influential in treating war wounds, and debunking the formerly popular method of using harmful treatments to disinfect such wounds.

Student Reactions

Dr. Hanophy always knows how to capture the audience’s attention.” — Christine Johnson

“Dr. Hanophy always knows how to capture the audience’s attention with his passion for microbiology and his contagious smile,” said Christine Johnson, president of the SJC Brooklyn Science Club. “As a student in his microbiology class, it was interesting to see how innovative the scientists, including Alexander Fleming, were in order to find a better way to treat the infected wounds of soldiers in the First World War… As the Science Club president, I could not have asked for a better event to start off the year!”

“During Dr. Hanophy’s presentation, we learned about the discovery of biofilms and the development of ‘artificial wounds’ by bacteriologist, Alexander Fleming,” said SJC Brooklyn Science Club Vice President Juanita Arias. “For instance, Dr. Hanophy expressed that prosthesis-related bacterial infections are correlated with biofilm infections. These infections are highly resistant to antibiotics. Thus, increasing understanding of biofilms is vital for the treatment of diseases caused by different bacterial cells living in the same community.”