Modern innovators like Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg certainly deserve their pages in the history books, but perhaps they haven’t earned as lengthy a write-up as you’d think, says Department of History Assistant Professor Peter Maust, Ph.D.

“Historians and other scholars have been fighting tooth and nail against (idolizing single innovators) for decades,” Dr. Maust said during his liberal arts colloquium Sept. 26 at SJC Long Island. “There’s a big argument that you can’t take technological changes out of their historical context by just putting all this weight on one genius.

“You’re setting aside all the other advancements that needed to happen in order for (a Gates or Zuckerberg) to be successful,” he added.

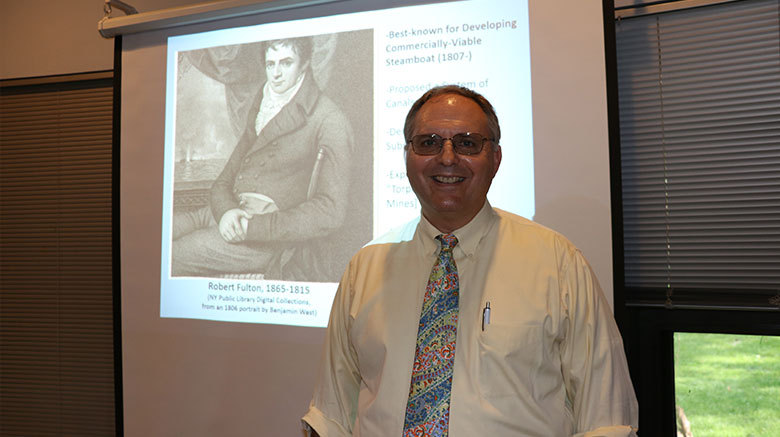

Dr. Maust’s lecture, “Inventive Activity in the Early United States and the Heirs of Robert Fulton,” discussed the historical significance of 19th century inventor Robert Fulton.

This image of the inventor as somebody who does something for the public good was molded in the time of the 1800s. And in part it was molded by Fulton and the success of steamboats.”

Though not a household name to many, Fulton, who is widely credited with developing the first commercial steam-powered boat, revolutionized travel and commerce in the early United States, and played a crucial role in the country’s territorial expansion and development.

His legacy is immortalized in marble — a statue of Fulton sits at the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol — and in the famed painting “The Apotheosis of Washington,” found in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol Building. But his predecessors aren’t nearly as admired.

“Fulton was extraordinary, but he had access to 20 years of failures that he studied,” Dr. Maust said. “He had access to previous patents. He had access to all this work, and he worked on it a while before he was able to make it functional.”

While Fulton’s celebrated status lives on to this day, Dr. Maust attests that the modern day “heroic inventor” persona was not developed until around the Fulton-era in the early 19th century.

Dr. Maust asked the audience gathered in the Shea Conference Center to put themselves in the mindset of Americans in the early 1800s, when “a general skepticism of technology was popular to the time” and there were no perennially celebrated iPhones or app inventors. It was a time where technological progress was nowhere near as valued by the public. Dr. Maust posited that, before Fulton, innovators and inventors were seen less as Steve Jobs-types, and more as visionary cranks.

“This image of the inventor as somebody who does something for the public good was molded in the time of the 1800s,” Dr. Maust said. “And in part it was molded by Fulton and the success of steamboats.”